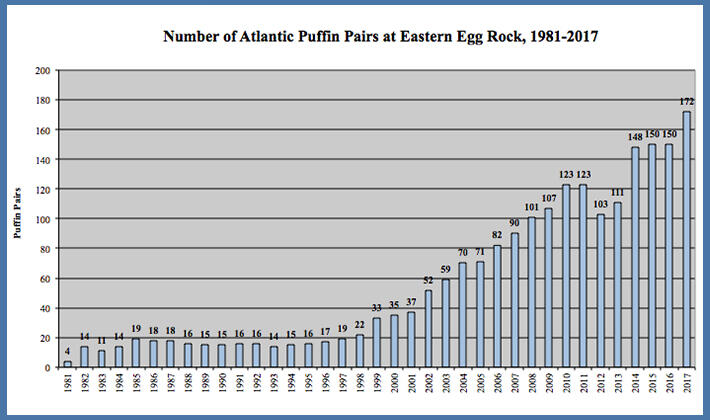

Eastern Egg Rock Puffins increase to 172 pairs

2017: One of the best years for Maine puffins

The Eastern Egg Rock puffin colony increased from 150 to 172 pairs during the 2017 nesting season, further supporting the link between cooler water and puffin breeding success. The 22-pair increase at this southernmost Maine nesting colony is the highest one-year bump in the nesting population since puffins first recolonized Egg Rock in 1981. The increase occurred during slightly cooler sea surface temperatures (SST)—which apparently set the stage for abundant forage fish near the island.

In 2017, the Gulf of Maine SST was just a half degree Centigrade cooler than the same period in 2016. This small drop in temperature coincided with a notable increase in puffin nesting success.

Puffins and Plankton

While its increasingly certain that puffins have more nesting success in summers when sea surface temperature is cooler, the link between the cooler water and nesting success is complex. One intriguing possibility is that puffin nesting success is tied to the timing and location of concentrations of phytoplankton (microscopic floating plants such as algae and diatoms). When conditions such as water temperature, day length, salinity, and nutrients coincide in the right place, the chlorophyll bearing phytoplankton can multiply in huge numbers called blooms and this typically sets the stage for blooms of zooplankton (microscopic animals such as copepods and other floating animal larvae). These feed the small forage fish required by puffins. In this way, puffins are intimately connected to the presence, abundance and timing of plankton blooms.

According to Dr. Kevin Friedland of NOAA, the Eastern Gulf of Maine experienced a larger and later than usual spring bloom of phytoplankton. This provided ample food for the copepods and other zooplankton that in turn feed the small white hake, Atlantic Herring, sand lance, and other small fish that puffin chicks depend upon. The map to the right shows chlorophyll densities as captured from satellite views of the Gulf of Maine. The bloom pattern in 2017 was notably different from the average phytoplankton distribution in the years 1998-2013 which showed low magnitude blooms in eastern Gulf of Maine.

Although the three puffin colonies managed by Project Puffin are just south of the areas shown in dark green, the prevailing currents move plankton in a westward, clockwise direction closer to the nesting islands. The later than usual bloom of phytoplankton this year was also desirable because there has been a trend of increasingly early phytoplankton blooms and this pattern has resulted in an asynchrony with the zooplankton (e.g. copepods) that feed on the phytoplankton. The spring plankton bloom is on average two weeks early than it was in 1982 when satellite mapping of plankton blooms began. The year 2005 marked the beginning of a trend toward earlier spring plankton blooms. It is likely that a later than usual phytoplankton bloom in the spring of 2017 reduced the gap between phytoplankton and zooplankton blooms, favoring a robust crop of zooplankton and better than usual food supply for the small fish for puffin chicks.

Other Gulf of Maine puffin colonies also had a good year

Puffins nesting at nearby Seal Island NWR and Matinicus Rock had a similarly good year. At Seal Island, 86% of the puffin pairs successfully fledged a chick—one of the best seasons ever recorded for this restored colony. In sharp contrast, during the warm water summers of 2012 and 2013, only 30% and 10% of pairs, respectively, fledged chicks. This year, Seal Island's puffin chicks had a good supply of high quality food, with white hake, Atlantic herring, sand lance, and haddock comprising most of the diet. Poor foods such as butterfish and sticklebacks were rarely brought back to any of Maine's puffin islands this year.

Likewise, 80% of the puffin pairs at nearby Matinicus Rock successfully fledged a chick on a diet of mostly white hake, sand lance, and haddock. While Acadian redfish was an important part of the diet in 2016, it was rarely fed to chicks last summer. In this food-abundant year, Project Puffin's resident biologists and interns were thrilled to find consistently fat chicks right up until fledging day. During 2012's ocean heat wave, Matinicus Rock’s fledgling puffins weighed only about 250g. In contrast, this year's fledglings averaged 350g. On the Canadian border, Machias Seal Island's puffins also did well, with 55% of puffin pairs fledging chicks—far better than the 12% that fledged chicks in 2016.

The Bigger Picture

Although most of the Earth's oceans are warming due to human-caused climate change, the Gulf of Maine is noted for being one of the fastest-warming marine habitats on Earth. Maine's puffins, already at the southern limit of their range, serve as sensitive indicators of the effects of SST. The pattern in recent years is that warmer water and increased run-off from rivers contributes to smaller and earlier phytoplankton blooms. In these conditions, white hake and Atlantic herring move to cooler water to find food, resulting in fewer of the puffins' preferred forage fish.

With insufficient food, puffins fledge fewer young; those that do fledge head off to sea without the fat reserves needed to survive and this leads to a trend of fewer puffins returning to join the breeding population in recent years. But as this year's nesting season demonstrates, the news for puffins is not all grim. Due to successful fisheries management, two commercially important forage fish—Acadian redfish and haddock—are on the rebound, following decades of overfishing. In 2016, puffins at the southernmost Maine colonies made good use of Acadian redfish. Haddock is the other "rising star" forage fish. Prior to 2010, haddock was not part of the Maine puffins' diet. Since then, however, it has become a regular part of puffin chick diet. In 2017, haddock made up 14%, 10% and 6% of the foods fed to puffin chicks at Seal Island NWR, Matinicus Rock, and Eastern Egg Rock, respectively. This demonstrates the importance of well-managed, sustainable fisheries, and gives us hope that a more diverse diet will help the puffins adapt to their changing ocean home.

| EER and Puffin History |

|---|

| Puffins were hunted for feathers and food at Eastern Egg Rock until the last birds were killed in 1885. Except for a few at nearby Matinicus Rock, by 1900 puffins no longer nested in mid-coast Maine. To restore the colony, Project Puffin translocated 954 chicks from Great Island, Newfoundland to Egg Rock from 1973 to 1986. An additional 950 were moved to Seal Island NWR—another nearby, historic puffin nesting island. |

|

In 1973, six pairs nested at Egg Rock, eight years after the first chicks were moved to the island. The tiny colony remained dangerously vulnerable until 1999 when numbers began to slowly increase—a pattern that continued until 2012. Since 2012, the number of nesting pairs has fluctuated along with changes in sea surface temperatures (SST). In warm years, fewer pairs nest; many that attempt to nest either fail to hatch a chick or rear a lightweight chick. By contrast, in cooler years, puffins rear more chicks, which usually grow faster and reach higher weights—a key attribute that helps them survive at sea. |

Learn about birds and take action

Adopt-A-Puffin

Adopt now and receive: A Certificate of Adoption, A biography of "your" puffin, and The book How We Brought Puffins Back To Egg Rock by Stephen Kress.

Visitor Center

The Project Puffin Visitor Center (PPVC) is located at 311 Main Street in downtown Rockland, Maine. The center opened its doors officially on July 1, 2006.